The Fortingall Yew – Europe’s Oldest Living Tree?

The ancient yew tree that stands in the churchyard in Fortingall must surely be one of the most written-about and photographed trees in Britain, attracting visitors all year round. Estimates of its age have ranged from 2000 years to as much as 9000 years, and at the time of the Millennium the figure of 5000 years was settled upon. Yet within the last forty years the Guinness Book of Records declared the Fortingall Yew to be ‘the oldest living vegetation in Europe’ and gave its age as ‘c.3500 years,’ so the sudden increase was something of a mystery!

Yew trees in Britain, including the one at Fortingall, featured in the media on several occasions in 2019, with news that ancient trees once estimated as ‘up to 5000 years old’ may stand to have a few millennia lopped from their branches! No one can be certain of the age of the Fortingall Yew because the usual techniques deployed by archaeologists for dating timbers cannot be used. In common with most ancient yews, the heartwood in the centre of the original tree decayed long ago, making it impossible to either count the growth rings or use radiocarbon dating of the earliest rings for estimating the yew’s age.

A new system of aging has led experts to conclude that the trees may be centuries younger than originally thought. The claims were published in the July 2019 issue of the Royal Forestry Society’s quarterly journal. Researchers from the Ancient Yew Group and several universities have made extensive studies of ancient yew trees in Sussex, uniting different methods based on tree-girth, tree-rings and historic rates of growth.

Making allowance for the irregular rate of growth in very old yews, the combined methods give a more complete picture. If the new ‘Unified Field Theory’ is applied to the yew at Fortingall then it would be dated at around 2000 years of age. However, it can still comfortably hold onto its title as the oldest tree in Britain, if not Europe.

The rotting of the core wood in a yew tree is not an indication of its imminent demise: it can continue growing for many hundreds of years more. As the pressure of the weight increases on the outer shell of the trunk, the tree reacts by putting out vigorous new growth in the stressed sections. Even in the last stage of the life of the tree, when the hollow trunk may collapse, new shoots can still appear from the stump or the roots.

Depending on their environment, yews can be among the slowest growing trees on Earth. In extreme habitats, where they are exposed to low temperatures and strong winds, the annual growth can even stop altogether for a period. A dead-wood sample from a yew growing on a cliff in Cumbria revealed 220 rings in a radius of only about 16 mm [3/4 in]. The average mature yew increases its girth at the rate of about 1 cm [1/2 in] a year. But yew trees often have several trunks, which may be deeply grooved or twisted, making it very hard to get an accurate count of the growth rings.

The intense demand for yew wood to make bow staves for use by military archers during the Middle Ages led to mass felling of yews all over Europe, and the yew population has never recovered from this. Some western European countries have less than a dozen ancient yews remaining. Britain is fortunate — it’s estimated that today about 450 very ancient yews exist in this country, of which the Fortingall Yew is undoubtedly the most celebrated. The Fortingall tree is likely to be the oldest specimen, and possibly the oldest living vegetation in Europe. European yews [Taxus baccata] belong to a family of four species worldwide, and are indigenous to Britain. A fossilized yew twig found at Whitby dates to the Lower Jurassic period of around 170 million years ago.

Yews are commonly found in churchyards in England and Wales, although less so in Scotland. They have long been associated with mythology and rituals concerning life and death, some of which were in practice until comparatively recently.

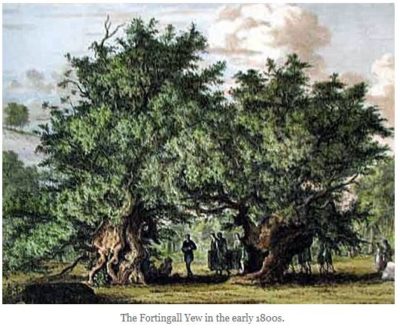

The 18th century Welsh traveller Thomas Pennant was the first to write about the Fortingall Yew in A Tour in Scotland in 1769, published in 1771. He measured the dimensions of the trunk of the ‘prodigious yew’ and recorded it as 56 ½ feet in circumference and 18 feet thick. His companion Moses Griffiths made a crude sketch of the tree, later worked up into an illustration for the book. It shows that the heart of the trunk was decayed almost down to the ground, nearly dividing the tree into two, but plenty of healthy growth is springing from the two sections. Pennant mentions that within living memory the height of the trunk had been 3 feet and that Captain Campbell of Glen Lyon had told him that as a boy he had often clambered over or ridden through the gap.

Remarkably, in the same year another traveller, an English barrister named Daines Barrington, also visited the Fortingall Yew and measured it. He recorded the girth of the trunk as 52 feet, but the discrepancy may be due to the fact that young growth in yews often sprouts at the base of the trunk, making it difficult to get an accurate measurement.

Given the hollowing out of the trunk by decay, it’s not surprising that in 1838 in The New Statistical Account of Scotland the minister of Fortingall, the Rev. Robert McDonald writes, ‘What remains of the celebrated yew tree of Fortingall Churchyard appears as two distinct trees some yards distant from one another.’ He went on to say that when he commenced his incumbency in 1806 there lived in Fortingall a man of at least 80 years of age, ‘who declared that when a boy going to school he could hardly enter between the two parts, now a coach and four may pass through them…the dilapidation was partly occasioned by the boys of the village kindling their Bealtain at its roots.’ [The tradition of lighting a bonfire at the Celtic festival of Beltane – though not at the roots of the yew tree — continued in Fortingall until 1924, when the head keeper on Glen Lyon estate banned it because the whin bushes growing on the hillside behind the village, which were being raided for fuel, were needed to provide shelter for the pheasants.]

The yew bears a very different appearance in an etching published in 1822 in a volume named Sylvia Brittanica by the landscape painter and engraver Jacob George Strutt. It shows the two halves of the tree trunk, both substantial in girth and bearing luxuriant foliage which joins together at the top, with a wide gap in the middle of the trunk through which a funeral procession with coffin bearers is passing. However, there is no certainty that Strutt ever visited Fortingall, and it’s likely that he relied on verbal descriptions when he made his etching. He mentions that it was a local custom for funerals to pass through the gap in the yew when entering the churchyard, although as by this time a protective wall had been built around the tree his information was somewhat out of date!

An Edinburgh physician, Sir Robert Christison, published a detailed study of the Fortingall Yew in 1879, and mentioned that a Dr Irvine of Pitlochry had told him that when his mother was a girl, in about 1785, she could easily squeeze through the gap in the tree and that her father had had a wall built at that time to protect the tree from souvenir hunters.

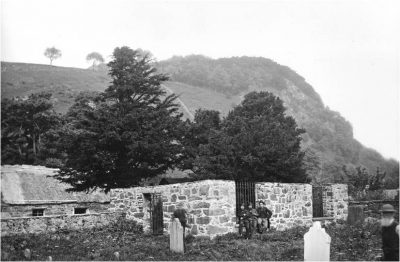

The wall was urgently needed! As the fame of the tree grew various legends accumulated around it, including the curious one that Pontius Pilate was born in Fortingall and had played under the tree as a boy. More and more visitors wanted mementoes, and locals were happy to supply them. Yew wood is attractive, a variegated reddish and pale yellow in colour, and easy to carve or turn. Large branches were cut from the tree – one writer mentions no fewer than 14 saw cuts – and turned into ‘drinking cups and other curiosities’ to sell to tourists. The first wall was replaced in the early 19th century by the very substantial one which still stands today, with openings guarded by railings for viewing. It appears on a map of 1833.

Although today we think of the Fortingall yew as growing in the churchyard, it clearly predates the present church by many centuries and also the earliest church on the site which dates to the late 7th century. Fortingall was an important Christian centre at this time, the new religion having been brought to the area by Irish missionaries coming from the monastery on Iona. It’s known that the founders of early Christian settlements and churches often established them on sites that were already regarded as sacred by the pagan people they came to convert. St Columba [521-597], whose biographer St Adamnan [624-704] brought the Christian faith to this area, is recorded as having preached under a yew tree on the Hebridean island of Bernera. As early as 1184 AD the presence of yew trees in burial grounds and holy places in Ireland was recorded. The ancient yew in Fortingall would already have had sacred significance, perhaps as the focus of pagan worship. The Gaelic word ‘bile’ means ‘sacred tree’ and forms part of local place names such as Coshieville and Tullochville.

No doubt owing to their longevity, yew trees have long been associated with death and immortality, hence the old custom of funeral processions going through the one in Fortingall. There are references to yew branches being placed in graves in pre-Christian times, and the rubbing of the bodies of the dead with yew leaves. In Shakespeare’s play Twelfth Night there is a reference to ‘ a shroud of white stuck all with yew’. The Old English name for the tree is ‘eugh’ which came from the Old High German words ‘iwe, iwa’. It is tempting to see a link with the Old High German ’ewi, ewa’

meaning ‘eternity’.

The parents and ancestors of Major-General Stewart of Garth rest beneath the spreading branches of the Fortingall Yew, as does the Rev. Duncan Macara [1754-1804] who was minister at Fortingall for 50 years and did much to restore peace to the area in the troubled times following the turbulence of the Jacobite uprisings. His grave and headstone lie in a small triangular enclosure to the east of the main enclosure around the tree.

The Fortingall Yew is a male tree and so does not bear berries. A female tree stands next to it in the private burial ground of the Currie family and is covered with a rich crop of red berries [the botanical name is ‘arils’] each autumn. However, in November 2015 the male yew attracted widespread media attention, even featuring on the BBC news, because Dr Max Coleman, a scientist from the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh [RBGE] spotted a branch near the crown that was carrying three berries! This ‘sex change’, as it was dubbed by the media, is not unknown among yews. Dr Coleman commented, ’Odd as it may seem, yews, and many other conifers that have separate sexes, have been observed to switch sex. It’s not fully understood – normally the switch occurs on part of the crown rather than the entire tree changing sex. In the Fortingall Yew it seems that one small branch in the outer part of the crown has switched and now behaves as female.’

The three berries were taken to the Botanic Garden at Edinburgh and planted in the hope that they will germinate, as part of a project to conserve the genetic diversity of yew trees around the world.

Clippings from the tree have also been taken to the RBGE to form part of a mile-long yew hedge.

Doubtless people will continue to dispute the age of the Fortingall Yew for years to come, with no one able to provide conclusive proof, and it will continue to attract the visitors from all over the world who come to gaze in awe at one of the oldest of all living things.

Fran Gillespie

October 2017

Updated October 2019

Belfast Yew

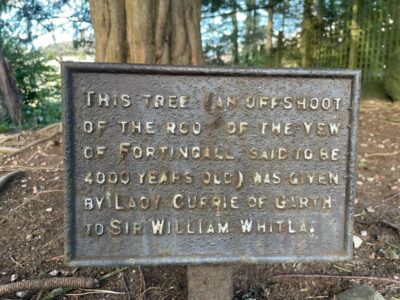

There is a yew in Belfast that has grown from an offshoot of the Fortingall Yew, said to have been given by Lady Currie of Garth to Sir William Whitla.

Sir William Whitla (1851 to 1933) was “one of the most significant figures in Ulster medicine of any era, with an outstanding career, and a legacy which was quite considerable. No consideration of the history of Ulster medicine, nor of Queen’s University, Belfast, can fail to accord him considerable importance and these were the areas of only two of his distinguished achievements”. “On his death Whitla bequeathed his house in Lennoxvale to Queen’s University as a residence for the Vice-Chancellor” (1). Whitla’s former home has grounds and garden that are relatively unknown to the public.

Although Scottish, Sir Donald Currie (1825 to 1909) had close connections to Belfast through the ships of the Union-Castle line built at Harland and Wolff’s shipyards. He was given the Freedom of the City of Belfast (2).

References

1 https://www.newulsterbiography.co.uk/index.php/home/viewPerson/2033

2 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_Currie

Recommended general reading

Yew by Fred Hagender. Pub. Reaktion Books 2013, ISBN 978 1 78023 1891

Ancient Trees: Trees That Live for a Thousand Years by Edward Parker & Anna Lewington. Pub.

Batsford 2012, ISBN 978 1 84994 0580

Associations

Ancient Yew Group: www.ancient-yew.org

The Woodland Trust and the Ancient Tree Forum: www.woodland-trust.org.uk

www.ancient-tree-hunt.org.uk