Fortingall Parish Church

There is a long history of religious activity associated with Fortingall and its surroundings (see ‘History’). A Celtic hand bell, first recorded in the manse in 1881 and fragments of four early medieval cross-slabs point to ancient origins. In addition to the cross-slabs. there are several cross-incised stones in the burial-ground. These finds evidently imply an early Christian site of some significance and aerial photography has revealed that the church stands roughly at the centre of a large rectilinear enclosure, perhaps the vallum of a monastery.

Following the Reformation in 1560, Scottish churches, especially in the country, were simple structures which reflected the puritanical spirit of the times. They were typically long, narrow and low with a door and windows in the south wall, a bare earth floor and no seating. To this basic ‘preaching box’ in Fortingall, a belfry was added in 1768 (and can now be seen in the churchyard). Around 1850 a north extension and three galleries were added along with a raised wooden floor and, on the west gable, a small vestry.

The church itself has been rebuilt a number of times. Photographs from September 1884 show a much more modest structure with the 1768 bellcote on the west gable (Erskine Beveridge Collection http://canmore.org.uk/collection/747849).

The New Church

The present appearance of the Church is due almost entirely to the influence of Sir Donald Currie. By the end of the 19th century the building was in a poor state of repair with particular concern about the roof. In 1899, Dunn and Watson drew up plans for its renovation and modernisation but these were rejected in favour of a completely new building which they designed in MacLaren style. Built to the highest standards by John McNaughton of Aberfeldy – mainly at the expense of Sir Donald Currie – it was formally handed over to the Heritors on 23rd September 1902.

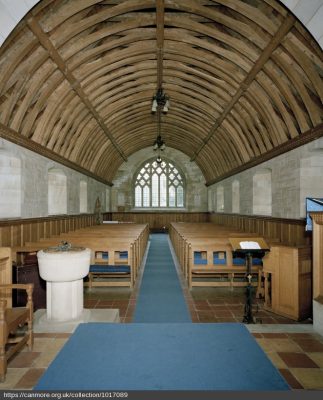

The architects designed a larger, simple Scots Gothic church of nave and chancel, with a re-creation of the original bellcote on the chancel arch. MacLaren’s plans for the village incorporated elements of Scottish medieval buildings and the church displays some of these – it is harled and has crow-stepped gables. Dunn and Watson incorporated some of the fabric of the earlier church on this medieval site. The simple building consists of a chancel and nave with a south porch. The bellcote towards the east end of the church is in 18th Century style and reproduces the design of the one on the earlier church. The Arts and Crafts interior is of the highest quality with all the original fixtures and fittings, including an open barrel vaulted timber roof. On the inside, the walls are sandstone, with oak panelling . The roof is of hand-worked oak timbers in an open barrel-vault. The pews and other furnishings are also of oak, as is the chancel screen, designed by Sir Robert Lorimer, which, along with stone tablets of the Lord’s Prayer and Ten Commandments were erected as a memorial to Sir Donald Currie by his family in 1913.

Details were recorded by the Threatened Building Survey prior to a programme of restoration, which included the relocation of the 1768 bellcote. The church forms an important element in the unique estate village of Fortingall.

On a window-ledge on the north side of the nave is the bell from the previous church. It was cast in 1765 by Johannes Specht of Rotterdam who also made bells for Paisley Abbey and Portsoy Parish church. In a niche behind the pulpit there was until 2018 a quadrangular hand-bell made of iron coated with bronze probably dating from the 7th Century. While it may or may not have belonged to St Adamnan, it is of a type common in Ireland and used by missionaries of the Columban church from Iona. A similar bell can be seen in Glenlyon church.

Pictish Stones

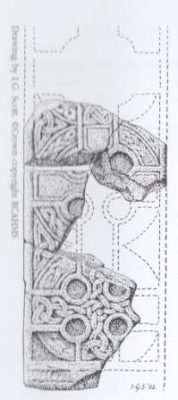

Fragments of Pictish cross-slabs discovered during demolition of the old church in 1901 were mounted in the chancel in 2002. Although

sadly broken up, the stones retain crisp carving as a result of protection from the elements for many centuries (at least three of the stones

were found in the walls of the old church). The stones, dating from around 800 AD, do not include Pictish symbols but are decorated

with interlacing, key patterns and triquetra knots. On the back of one stone are parts of robed figures, perhaps clerical and consistent with an early monastic site. The stone on the north wall behind the pulpit is made up of three linked, equal-armed, ringed crosses: it is very rare type – the only similar slab is in St Andrew’s cathedral.

The slabs are all of a fine grey sandstone which is not local and may have come from Strathmore where similar Pictish cross-slabs were produced and can be seen at Meigle. Common design features suggest that the Fortingall stones were carved by a single school of masons if not by the same craftsman.

Fortingall Parish

In 1585 the parishes of Glenlyon and Kinloch Rannoch were joined to Fortingall to form an area of almost 300 square miles. In 1845 Glenlyon and Kinloch Rannoch separated; and following the Disruption of 1843 and the founding of the Free Church, there were two churches in Fortingall for about a hundred years. In 1954, Glenlyon was again linked to Fortingall and since 1980 the two have formed a single parish. For a short time they shared a minister with the parish of Dull and Weem, but since 1990 Fortingall and Glenlyon has formed a single linked charge with the Lochtayside parishes of Kenmore and Lawers. Originally the parish was almost entirely Gaelic speaking; 100 years ago Gaelic was the first language of about 75% of the people of Fortingall, but it has now been replaced almost entirely by English.

Graveyard

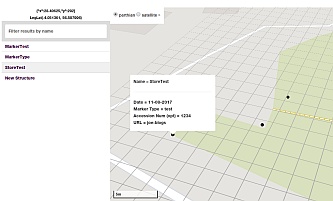

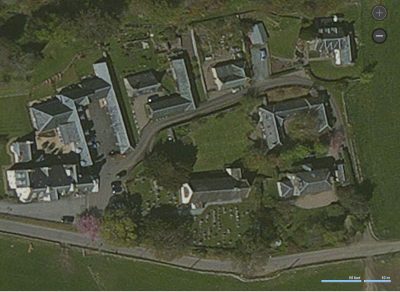

The graveyard lies mainly on the south and west sides of the church as seen in the satellite photograph (Microsoft Bing).

. To the north west is the ‘Currie enclosure’ named for the family of Sir Donald Currie whose memorial in the form of a free-standing cross stands in the enclosure. On the south west side is the ‘Chesthill enclosure’ containing the 1768 bellcote. Beyond the graveyard wall is the War Memorial.

Behind the porch is a large stone font of primitive form. Until 1901, it was situated within the church and used for baptism. Early medieval fonts of this type are common in this area with other examples in Fearnan, Killin and Dull.

Standing against the south wall of the church, is a stone with a simple incised cross probably of 7th Century date. Such slabs are common in Ireland and in the ancient Scottish Kingdom of Dalriada in Argyll suggesting that it was created by early missionaries from Iona. Until 2002 this stone formed the threshold at the Kirkyard gate and still bears the mark of the iron gatepost. Next to it is an early medieval slab deeply incised with three crosses. In the kirkyard are several such slabs which appear to have been a local peculiarity.

The armorial stone set into the south wall of the church is the gravestone of ‘James Ross, Minister at this Kirk…’ who died in 1636 and was buried in the old church.

To the east of the church is the somewhat neglected burial ground of the Campbells of Glenlyon. Robert Campbell (1632-1696) was notorious as the commander of the government troops at the massacre of Glencoe.

Peter Heyes

Source Acknowledgements

The text has been adapted from a booklet titled Fortingall Kirk and Village (2015) whose main contributors were Dr. G. Stark and Mr. N. Hooper. Additional material is from https://canmore.org.uk/site/24964/fortingall-parish-church#804959, the ‘RCAHMS Excursion Guide 2004’, RCAHMS (STG), 2002; https://canmore.org.uk/site/24964/fortingall-parish-church and from http://taylyonchurches.org.uk/fortingall-church/.

The images of the interior of Fortingall church were taken in 2002; both are from Canmore (http://canmore.org.uk/collection/1036531 and http://canmore.org.uk/collection/1017089)

Show the Map