Fortingall’s Historical Context

Prehistoric Fortingall

The name Fortingall, first recorded as Forterkil, appears to be derived from the Gaelic words fortair (a stronghold or high ground) and cil (a cell or church). The Vale of Fortingall is a fertile valley surrounded by mountains but easily accessible, from both east and west coast, by a network of lochs and glens. Archaeology shows us that for more than 5000 years, the area has not only been inhabited but also regarded as a sacred place.

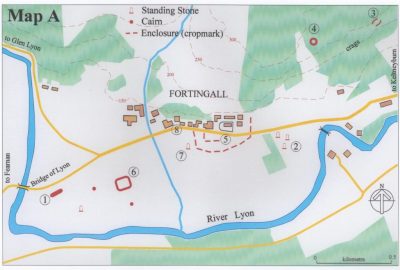

The possible long cairn (Map A location 1 above) is a feature that might date from the Neolithic Period (4000-2000 BC) although there is currently no archaeological or dating evidence to support this possibility (https://canmore.org.uk/site/24999/fortingall) . If Neolithic it would have served as a communal burial place for important people for centuries. Possibly dating from the same period are numerous large stones with cup marks cut into them. Their significance is obscure but they may have served as boundary markers. An example can be seen in the churchyard.

The Bronze Age (2000-500 BC) saw the construction of ritual monuments including standing stones and stone circles. In the field 300m east of the church are three groups of three standing stones (location 2). Excavations have shown that two of these groups were sub-rectangular settings of eight stones with the largest at the corners. The finding of a Victorian beer bottle beneath one of the stones suggests that they were deliberately toppled and buried in the late 19th century.

The site of the double-ditched hill fort above Balnacraig was probably occupied throughout the Iron Age (500 BC-500 AD). The Caledonians who lived in this area would have used the fort for protection during this troubled period (location 3). Schiehallion, the “fairy hill of the Caledonians”, rises 5 miles to the north.

In the Early Christian period (500-1000 AD) massively walled circular homesteads were introduced to the area, probably by colonists from the west. Dun Geal (‘White Fort’) (location 4) is one of the best preserved in the district. Such sites were well protected but also had easy access to good arable and grazing land. These monuments reflect continual human activity over a period of 4000 years from the first farmers to the coming of Christianity. For much of that time the great yew tree would have been a venerated local feature.

The Pontius Pilate Myth. There is no evidence, however, for the strange tradition that Pontius Pilate was born in Fortingall following a visit by his father to the Caledonians as an emissary from the emperor Augustus. The Romans did not arrive in Scotland until Agricola’s campaigns around 80AD, and the eventual front line of the empire was along Strathearn and Strathmore.

Early Christian Fortingall

Several factors suggest that Fortingall was an important Christian centre as early as the 7th century AD. At that time, missionaries of Irish origin came from the monastery of Iona (founded by St Columba in 563) to preach the Gospel in the western Pictish province of Athfothla (a name surviving today in Atholl). St Adamnan (locally known as Eonan) was Abbot of Iona from 679 and is celebrated for his biography of St Columba. He is believed to have extended his activities from his first base at Milton Eonan, near Bridge of Balgie, down Glenlyon to Fortingall and later to Dull where the parish church was dedicated to him. Adamnan may have taken this route to summit meetings he attended in Northumbria concerning relations between the Celtic and Roman churches.

Fortingall kirk seems to have been dedicated to Coeti who was Bishop of Iona in Adamnan’s time. The Fair (Feill-math-Choedde) held in Fortingall on August 20th well into the 20th century was probably also dedicated to him. An alternative suggestion is that these dedications were to the English St Cedd, who was a disciple of Aidan of Lindisfarne. The old church of Kenmore, Inchadney, was named after Aidan.

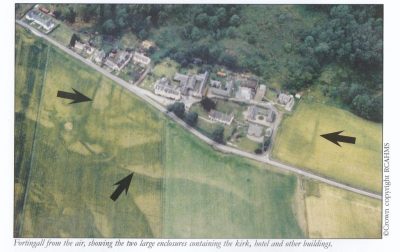

Compelling evidence of a large early monastic complex at Fortingall can occasionally be seen from the air in the form of crop marks, where now buried ditches cause the plants growing above them to ripen faster and grow higher than the surrounding plants (location 5). Aerial photographs show two large rectangular enclosures with rounded corners, with the church near their centre.

More tangible signs of an early Celtic Christian settlement dating from the 7th century have been found. These include a monk’s hand-bell and cross-slab which could have been involved in early Christian worship, a Celtic baptismal font and fragments of early cross-slabs showing a combination of Christian symbolism and Pictish decoration. It is likely that the early Celtic church would have considered the ancient Fortingall yew-tree sacred. References to the Gaelic bile meaning sacred tree are found in local place names such as Coshieville and Tullochville.

The Middle Ages

The monastic settlement at Fortingall was eventually eclipsed by another lower down the valley at Dull. By the 12th century, however, a network of parish churches had evolved and that at Fortingall was thriving. Its patronage is likely to have come mainly from the medieval magnate who occupied the moated homestead between the village and Bridge of Lyon (location 6). Another reminder of the Middle Ages is Carn na Marbh (Cairn of the Dead). Surmounted by a standing stone in the field south-west of the church, it is traditionally the site of a mass grave for victims of the Black Death in the 14th century, reputedly buried by an old woman, sole survivor of the plague (location 7). ‘It is, however, possible that this cairn is on the site of a much older prehistoric burial mound which may have been re-used as a preaching mound by the Celtic monks.’

By the end of the 15th century, Stewart descendants of the Wolf of Badenoch had established a powerbase at Garth Castle while the Campbells were taking over in Glenlyon from the indigenous MacGregors. Their feuds in the 16th century were recorded in the Chronicle of Fortingall by James MacGregor, Vicar of Fortingall, later Dean of Lismore and an early collector of Gaelic poetry. Clach Mo-Luchaig: a large boulder to the east of the Molteno Hall, supposedly named after St. Moluag of Lismore, is said to be where scolding women were chained.

Post-Victorian Fortingall

The present appearance of Fortingall and its Church is due almost entirely to the influence of Sir Donald Currie towards the end of the Victorian era. From humble origins in Greenock where he began work as a shipping clerk at the age of 14 years, he came to establish his own shipping line and went on to make his fortune in South Africa as head of the Union – Castle Line. Typical of the new Victorian elite of self-made men, he sought political power and a place among the landed gentry. He was elected MP for Perthshire and purchased Garth Estate in1880; Glenlyon Estate, including the village of Fortingall, followed in 1885 and most of Chesthill Estate in 1903. He worked hard and invested heavily to improve the prosperity of his estates and the conditions of his tenants.

Sir Donald Currie engaged the promising young architect, James MacLaren, to transform the village from a collection of neglected thatched cottages to a model estate village. MacLaren, son of a Perthshire farmer, rejected the fashionable Scottish Baronial style and sought to incorporate elements of Scottish medieval buildings – including harling, corbelling and crow-stepped gables – in a new and modern style influenced also by the Arts and Crafts movement in England.

Peter Heyes

Source Acknowledgements

The text is adapted from a booklet Fortingall Kirk and Village (2015) whose main contributors were Mr. N. Hooper (History) and Dr. G. Stark (Church).

Show the Map